Charity Hospital, better known to New Orleans locals as “Big Charity,” is located at 1532 Tulance Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana. This hospital served as a resource to the low-income population, residents of color, and any individual who did not possess insurance in the Lower Mid-City area. The hospital was well known for it’s dedication to fostering and curating a space that encouraged learning that would not otherwise be feasible for marginalized identities. As previously mentioned, Charity Hospital was overtaken post-Hurricane Katrina by the creation of the multi-million dollar University Medical Center, LCMC Health, the Veterans Affair Hospital, and the LSU Medical Center. This shift that prioritized privitization left the Lower Mid-City community shaken and in disarray– without access to affordable medical care otherwise, it only amplified segregation through ulterior means in a space that was already deeply segregated.

Prioritizing Privatization

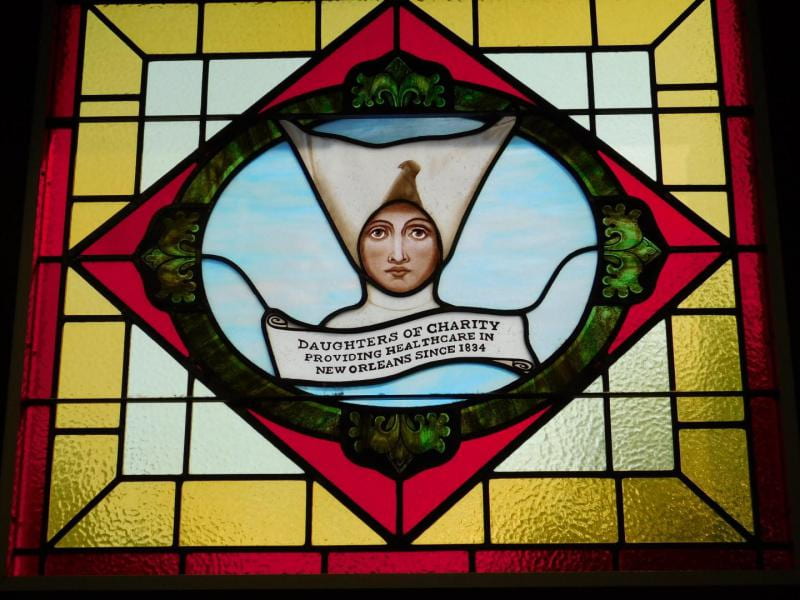

Charity Hospital derived its existence from The Daughters of Charity, a group of religious women that focused on paving the path towards spiritual healing through “saving souls.” In 1931, Huey Long, the governor of Louisiana, pushed for accessible and affordable health care at Charity Hospital. The hospital focused on providing accessible care, Anne Lovell states in Debating Life After Disaster: Charity Hospital Babies and Bioscientific Futures in Post-Katrina New Orleans how, “most of the New Orleans area low-income, uninsured care took place in Charity Hospital inpatient facilities” (259). Individuals even described Charity Hospital as a “medical safety net” (Lovell 259) and discussed how the incorporation of the GNOBED facilities would lead to shifting health care to prioritize privitization, which would only further cause inequities in the area. With this in mind, it is important to discuss the demographics within New Orleans pre-Hurricane Katrina and post-Hurricane Katrina– according to Herve Leleu in Renovating Charity Hospital or Building a New Hospital in Post-Katrina New Orleans: Economic Rationale versus Political Will, the Black population of New Orleans shifted from 67% to 60% while the white population increased from 28% to 33% (93). The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina showed the lack of regard towards Black individuals that lived in New Orleans, specifically how the construction of new multi-million dollar medical facilities have long term ramifications on the individuals living in the neighborhood. For example, Leleu states, “…thus [citizens living in the mid-city neighborhood] incur costs without achieving any benefit in the course of the new hospital’s construction” (93). Leleu also discusses how many individuals believed there was no immediate need to rebuild Charity Hospital post-Katrina due to the fact that a public hospital was no longer needed. This can be explored through understanding the intersection between public and private sectors. In order to save money to allocate funds towards the construction of the new hospitals, thousands of hospital workers were layed off. Many individuals were left to fend for themselves once being layed off and in addition to this, they were already struggling with the ramifications of Hurricane Katrina. This further exacerbates the lack of regard towards residents living in this area. Leleu mentions how, “Patients, predominantly the African American population and the poor, accustomed to going to CHNO for treatment now face the prospect of a new health care location, not knowing where to go, or having to travel greater distances” (93).