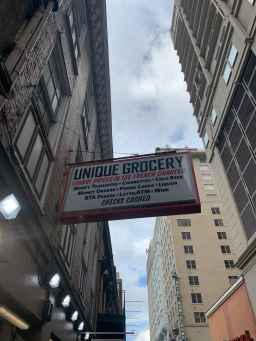

Before I arrived in New Orleans, I expected to make specific observations about environmental injustice. I anticipated looking into a lack of green spaces, the effects of climate events, and how housing disadvantages caused Black communities to experience them at a higher rate. Although I did observe that some communities are housed in areas that are more vulnerable to flooding, I decided to follow a different branch of environmental injustice: food insecurity. It’s when there is inadequate availability of nutritious foods, uncertainty about where food will come from and causes people to pursue different ways to gather food (Fitzgerald 4;Pyles, Kulkarni, and Lein 44). It disproportionately affects low-income households of women, Black, and Hispanic households, and in New Orleans, the “presence of food deserts” increases the food insecurity in the area (Pyles et al; Fitzgerald 8). Food deserts are areas that have “unequal geographic access” to nutritious, fresh foods and this was something I couldn’t help but notice in the city (George and Tomer). Within walking distance of my hotel, I noticed several convenience stores or restaurants as food options. The surrounding streets of the hotel was where I began my observations about the availability of food because the options made me consider if they were more suitable for locals or tourists. The food options were either fast food, touristy expensive restaurants, or liquor stores. They were convenient for visitors of the city, but not for the people who consistently visit Canal Street. New Orleans being a popular city to visit raises prices in general, but affordability is harder to achieve in areas that are focused on the satisfaction of visitors instead of locals. My observations pushed me to consider if an area with a concentration of tourists doesn’t have the best food options, what are the food options like in areas where tourists don’t visit? How can locals of the city maintain a balanced, nutritious diet in food insecure areas?

Since Hurricane Katrina, food insecurity has been a concern. In a research article exploring the food-gathering strategies of households before, during, and after Hurricane Katrina, the authors found that evacuees had to combine multiple food-collecting strategies to make ends meet (Pyles et al). They would share food by trading and bargaining, having meals together, and some households would give their extra provisions to families in need. However, these methods were not sustainable for long periods. Public and private food assistance programs were also an option for eligible households, but those who weren’t eligible or didn’t receive enough aid couldn’t rely solely on them. Additionally, a participant in the article described how the arrival of food from the National Guard was dehumanizing because it was thrown at them like animals (Pyles et al 50). Food assistance from the government was meant to help people affected by the hurricane but was unreliable to the point of pushing people to rely on multiple strategies to collect food. Relying on one channel of support was too risky for households, so combining any available strategies was the most resourceful option. Since Hurricane Katrina, there have been more hurricanes in Louisiana that continue to impact food-insecure households, and in 2017 the state had the second-highest rate of food insecurity in the US (Fitzgerald 4). Although it was almost twenty years ago, New Orleans is still affected by that disaster, and food insecure areas continue to increase.

Works Cited:

Fitzgerald, Kathleen J. “Hungry at the Banquet: Food Insecurity in Louisiana 2018.” (2018): 1-17.

Pyles, Loretta, Shanti Kulkarni, and Laura Lein. “Economic survival strategies and food insecurity: The case of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.” Journal of Social Service Research 34.3 (2008): 43-53.